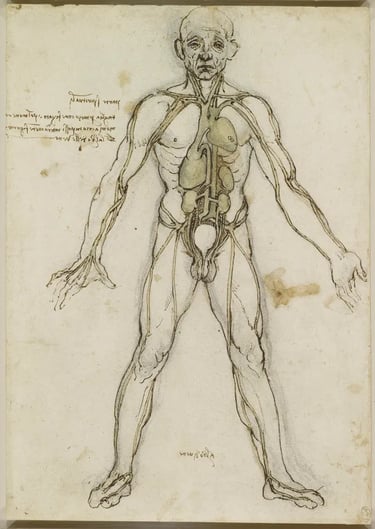

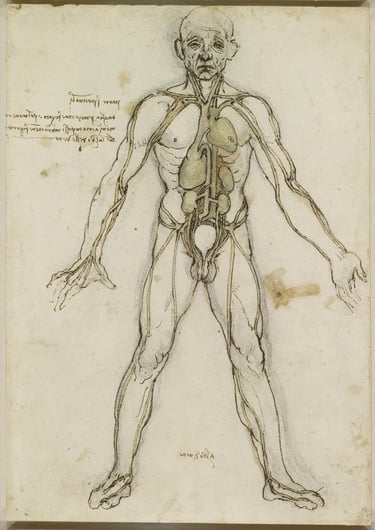

Leonardo has written a treatise on anatomy, showing by illustration the members, muscles, nerves, veins, joints, intestines, and whatever else is to be discussed in the bodies of men and women, in a way that has never been done by anyone else. All this we have seen with our own eyes; and he said that he had dissected more than thirty bodies, both of men and women of all ages.

– Antonio de’ Beatis

And every Generated Body in its inward form,

Is a garden of delight & a building of magnificence

– William Blake

Leonardo

Modesty is not for me, not with my bodies.

Those who have seen my drawings are like men introduced to the light, they smile and say they

would watch a dissection if they could

but in the moment of flesh their eyes would shred to see a body on the slab, flayed and quartered

and fearful to behold.

Few have the desire, few the stomach, few the means, few the patience, few the ability to draw

them with such rigor, and few whose only impediment is time:

only in me are all of these and so I should be the one to spend my nights with the dead,

breathless among the breathless comprehending shape and form, mechanics and construction

and proportion,

my eyes stunned at the true sight of our lucid unity, how we resemble the river or the forest or

the mountain,

the how of movement and the where of energy and the why of continued life or its undoing.

Who else has even thought of such a thing, who else could comprehend such nights?

*

The only patrons for these drawings are the dead and they cannot claim disappointment like the

living at how they look

or how I place the saints they ask for in odd landscapes where cave and color and atmosphere

matter as much as the holy body,

there is no confraternity to reject my final work, no collection of the well-meaning to question

my lack of symbols or suggest the pious story they would rather I tell.

Here in these rooms of huge silence our bodies are their own theology, their own defense, their

own solution,

but what I have gained in freedom and curiosity I have lost in all human companionship,

laboring alone for what no one has asked for and upon what few would ever want,

my friends here the dead now and the living to come.

To make a beginning in this work is to assume there will be no end and know that such

knowledge will never satisfy.

The gesture of Thomas’s hand into the side of Christ hints at this,

his eyes open to the reality of flesh even beyond resurrection and his eyes asking why God

should choose a body not once but twice –

for no one digging in the earth or building to the sky can go as far in their life as I do with one

body in a day,

turning it or myself to see it from every direction,

my fingers and hands covered in eyes as I dip them into the community of viscera and arteries,

nerves and tendons, muscles and bones and blood,

a mass of architecture and precision, of density and lightness, of the brittle and the soft and the

slippery,

all contained in the same kind of body I use to bend over and peer, and touch, as if trying to

comprehend the sun.

*

How many heads has it taken to draw this skull and draw it just so,

how many headless bodies must I beg pardon of,

and if I could hold them by the hair, glazed and preserved and their face facing mine

or commune with the weight of their gourd in my lap like some bloody prophet,

all as if I hadn’t had to destroy them in the making of my drawings,

so many heads cleaved or shorn or quartered, hemisphered or with the crown lifted off like a lid

(this the upper room or closet of our bodies walled with a pinkish contrast of nerves and jelly, the

brain our garret and seat of life leading to eyes and nose and mouth, to ears and curving

spine),

if I could do this more as magician than scientist, more seer than draughtsman, more

necromancer than merely curious as to the basic engineering which I believe begins here,

and if I could project light and sight from the eyes again,

would they approve of this intervening view of the skull that I’ve made, axis or geometric center

suddenly found in the head they simply held atop their neck?

*

And when I have filled a page with a sectioned skull – the right side whole but the left shaved

back and terraced from teeth to brow to show each further depth –

and when I have added beside such skulls sketches of single teeth,

and when I have scrawled in my haphazard way other notes in my own mirrored script –

I hold the skull and hold it closer,

I hold the skull and rehearse the labor of reducing it to this final state of severed and skinned and

scraped and come into my hands and out of my eyes and finally drawn,

and I hold the skull and wonder why it is that the skull holds me so in its sway,

why do I go to it and find life here rather than among the living who would comprehend nothing

of this trade, this work, this curiosity that to me is so essential,

and why does it still seem to live and why will the face it once held never leave my mind,

why can I not forget their bones any less than the look of their face when deceased or just ill and

near death and with these plans in my mind,

and why do I occupy a silent room in the night for their sake if not my own,

and to what end this gruesome brilliance

that I shudder and swell to comprehend God as much here as in the understanding of rivers or

flight,

and that the lifeless skull shudders too and assents and seems to nod, its own eyes straining to see

such a familiar but miraculous exposure?

I would prefer death to inactivity, and would prefer even more activity with the dead.

*

Some of my details are guesses, some of the angles and aspects of my drawings are no doubt not

only inaccurate but impossible

but the weight of my achievement is its ability to withstand the corrections

that will maintain rather than demolish what I’ve built.

Even my errors will hold others in awe, even what I’ve taken from earlier anatomists and can’t

yet suggest an alternative for

will light the way more deeply than the merely accurate and the never daring.

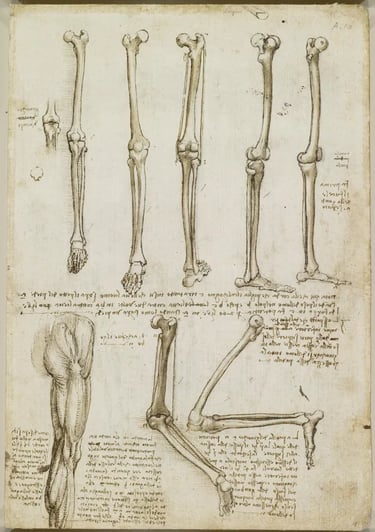

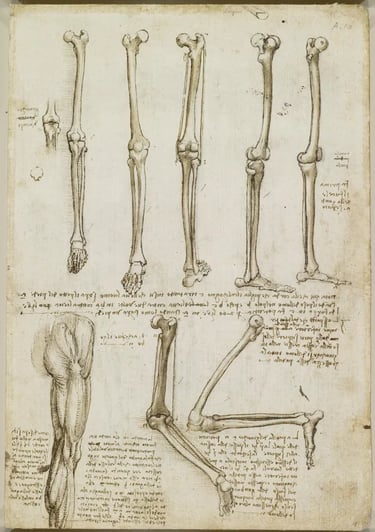

You will see from my youthful unfinished St. Jerome – posed as he is in a penitent crouch in his

usual wilderness – how my real theme is ever the neck and shoulder and arms, support and

measure and movement, fascination with rotation and force, the bend and the stretch,

and you will see the same from my studies of nature, to comprehend the breathing lungs of

ocean, the skeleton of rock and mountain, the veins of rivers and the entirety of all in the

rooted tree.

And have you seen our distant likeness beneath the paw of the bear or under the skin of the pig

or the monkey, or the place of learning that is a horse’s complete skeleton?

What is nature, what is animal life, and what else in the chain of being rhymes or nearly does

with our own basic form?

By now I know totality is impossible, I know that even an already selective view needs to be

further isolated and exploded onto ten more pages,

I know that if the entire body is one coil our depths are only more of them, coils within coils, the

most complex details alive in a fingernail’s space just as the simplest part is mirrored in the

sudden apprehension of the vast whole.

*

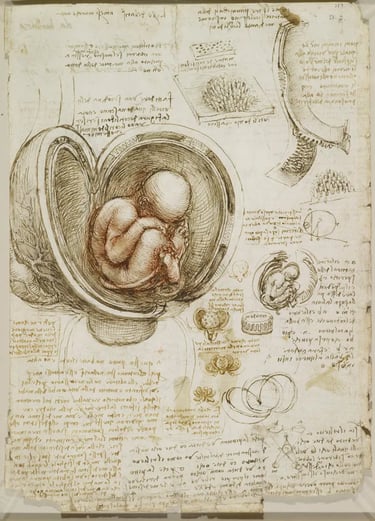

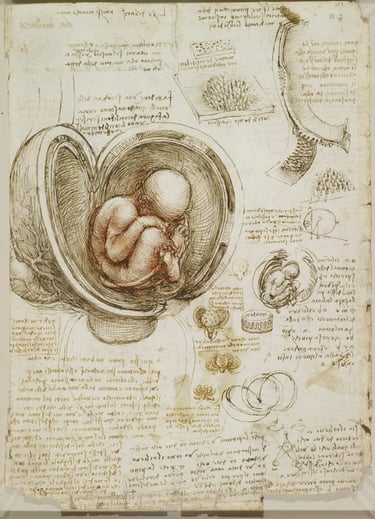

For obvious reasons I have not gone to our beginnings.

I have wintered with many brains and summered with thoughts of all the hearts I have held but a

human fetus has always been far from me

although I have seen our form miscarried – or otherwise – and have taken my eyes and tools to

it:

the vast process of the placenta, the beating and kick within the womb and the swelling,

all things my pen and ink cannot touch and which have eluded me, though I have guessed and I

have tried.

I would never distract the newest born or its mother with my obsessions,

I would never disturb the nursing or the nursed, fascinated and amused and confounded and in

love as they both are with each other.

Let the living live without the preoccupations of a ghoul forever following.

*

I was trained for painting and took to it so well that I rarely do it at all, there’s no need.

My teacher gave it up altogether when he saw an angel I made in youth

but I knew all the tricks even then and was storing up what I would need in old age.

I learned to draw only with a pen and quickly – repeatedly – to strengthen the real work which

takes place almost entirely in the head,

and I preferred to fill sheets of expensive paper with drawings rather than empty my years into a

painting that would cost me more in time and memory,

I found so much more while concentrating on a soiled wall or staring into the patterns of a stone,

some rock the world walks past.

When I was at work on my Last Supper and when to many I wasted whole days staring at the

wall while changing nothing

I also wandered Milan looking for the appropriate face for each apostle as well as our Lord,

and I ended up sketching quite a population, many men and many a demeanor, many noses and

foreheads and chins, many cheeks and wrinkles and curious looks,

local men at the market who never guessed they were under my pen since I brought the means to

sketch them swiftly.

In the past I went to the public bath to memorize the nudes

or I strolled the hospitals or brothels as much as the markets and taverns

or I followed the unusual body or face all day from a distance to see how he or she moved or

settled, smiled or grimaced or stood or turned –

and while I love beauty I don’t mean what is taken to be beautiful – a thing one can tire of – but

the real beauty that is accuracy tempered with rigor and somehow filled with rhythm.

This is why Giotto still lives, not because we copy him but because he copied nothing but what

he saw, because he was discovered drawing sheep on a rock,

and we insult him to trace his frescoes with humorless reverence rather than look out our own

windows.

*

In Florence I found the old man, aged beyond a century and sitting upright in the Spedale di

Santa Maria Nova,

his voice a clarity of decades and his body a monument to age, voice and body both still so

capable but lacking that important strength.

And so he died of nothing more than weakness, and here, I had spoken with him – here, his hand

had taken mine and now I was peeling it back

and wondering at the cause of so sweet a death indeed so sweet a long life that somehow tended

from the start to end with me beside him, taking him apart.

Alberti was the one who said that to portray the body truthfully one must begin with the bones

and branch out, clothing them slowly with sinew and muscle and skin,

that care for the body and curiosity in its working were required for even the most incidental of

figures,

but Alberti never met this old man and with him I saw it wasn’t art that I was doing,

and despite my reverence for Galen and Aristotle and Avicenna it is not science either:

it is an immense intimacy,

to ask how the bones are bound together,

how the muscles and tendons give movement to the bones, to the tips of fingers,

how the nerves bring sensation and the arteries nourishment, and how the whole is enclosed in

such total reactive and pliant skin –

and then so why have I left out how our flesh is also built for the touch others, why is the

question of human physical warmth only an aside?

*

Some of my pages are covered in faces, the same face over and over like a star held in the mind

in perpetual rotation,

head-on, from the back, below or either side, halved like a fruit or with every detail overlapping,

or inside and out concurrently as if I look with impossible eyes.

At some point the motive of symmetry will give way to the evidence of those eyes,

at some point every outward mirror – the tree of the heart, the branches of vessels, the vortex of

uterus akin to every spiraling braid, or everything within that recalls the sunflower seed or

the pinecone, all spiritual parts –

all of it will fall away in the face of the deceased and at some point the view of us as buildings or

grammar or numbers or maps will dissipate,

at some point I will refuse to distort what I see, refuse to harmonize it with art or abstraction,

with measurements or mathematics,

and I will forget the grid.

It’s the old view to take the measurement of our limbs and add or divide them with the rest of the

body’s numbers so as to finally see in it a thing of comprehensible wholeness

but peel back such numbers and apply them to the simplest worldly act and all I can do is

dumbly draw.

*

I have said before that many of us do not deserve the magnificence of our bodies and their

mechanisms,

I have said that the act of sex is sometimes so repulsive in the parts employed that our extinction

is only saved by the beauty of our bodies otherwise,

I have said that most of us are mere channels for food who offer no other purpose than the filling

of latrines

and in my life I have taken after Pythagoras and Plato in refusing to eat meat, refusing to be a

tomb for animals –

but my work with bodies has freed me from so much malice because there is a mystery about our

purpose,

because from the start my own painted Christ child was a chubby one, an earthy hungry human

being who chose to take on these joys and imperfections,

and that his last acts were at supper and in a garden, among dinner and the ground –

and peering now into a body that I may well have condemned as lazy when alive, I pause to see

that God made such a life as likely as any, and a life like mine almost never.

*

While my grandfather and uncle raised me I could walk to the growing house of my father’s new

wife

and did so as often as I could as a boy, from Vinci to Campo Zeppi,

and those hills were what I first loved, the life of the earth on that long walk, the plants and

animals and the contemplation, the language of weather and growth and light.

There is the memory of a cave out of the way, one I was astounded existed at all and how I bent

to look in and only saw darkness, only fear and desire,

and there is an earlier memory where a kite alighted on my cradle and with its tail it opened my

mouth and swept the inside of my lips with its feathers.

I think of that cave and that kite when I glance over the dozen drawn hearts that crowd one of my

pages like friends, they have been my friends,

so while it’s true that as a bastard any career of consequence was closed to me,

and while it’s true that my being barred from guilds and universities has filled with me with the

shame of all I lack in languages and culture

the kite and that cave and these hearts are the center of my gift, if I have one,

and it’s also in these bodies, in every indication of their lived lives, dirt still on the hands or the

full stomach or in the eyes,

and sometimes when I’ve finished with one I go to their head and I open their eyes

and I wipe the tears that I find there, I hold the hand as I rarely have in life, with no fascination

now but only with the tenderness of something shared.

Tim Miller’s most recent book is the essay collection Notes from the Grid. His other books include the poetry collection Bone Antler Stone, and the long narrative poem, To the House of the Sun. He is online at wordandsilence.com, and he talks poetry, mythology, and creativity on the podcast Human Voices Wake Us.

Listen to Tim Miller read and discuss his poem on his podcast

*If you are viewing this on mobile, scroll to the bottom of the page to listen to Tim Miller read and discuss his poem on his podcast